The Lynching Memorial - A Sacred Place

This placard greets you as you enter the newly opened Lynching Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. The memorial, the brainchild of Bryan Stevenson and his team at the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), sits on a 6-acre site overlooking Downtown Montgomery.

At first the words seem heavy and somber because while it’s called a memorial, my mind was still envisioning something more akin to a museum or some form of public art. A space where we acknowledge the past in a meaningful, artistic and educational manner. However, it becomes immediately clear the Lynching Memorial is more than that. More than any exhibit or memorial I’ve ever experienced.

Because the memorial is outdoors, it brilliantly uses the affect of the elements to enhance not only your experience, but the memorial itself. Once you enter, you are greeted by a concrete sculpture by Ghanian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo. The sculpture of enslaved Africans features iron chains, which have already rusted. The rusted chains highlight the indifference to human flesh, while also conveying the length of time the slave trade existed in the Americas. This installation forces you to acknowledge the brutality and violence of the slave trade and its impact on the family.

As you move your way through the outer courtyard, there are placards that provide you with historical context regarding the violence of slavery and the system of oppression it created. What I appreciated was there was enough information to provide you with context, but also spaces for you to sit and contemplate what you’ve read. They didn’t attempt to tell you the entire history of slavery and its legacy, but instead to provide you with enough information to appreciate what you were experiencing. I’m sure the hope is to pique your interest to learn more.

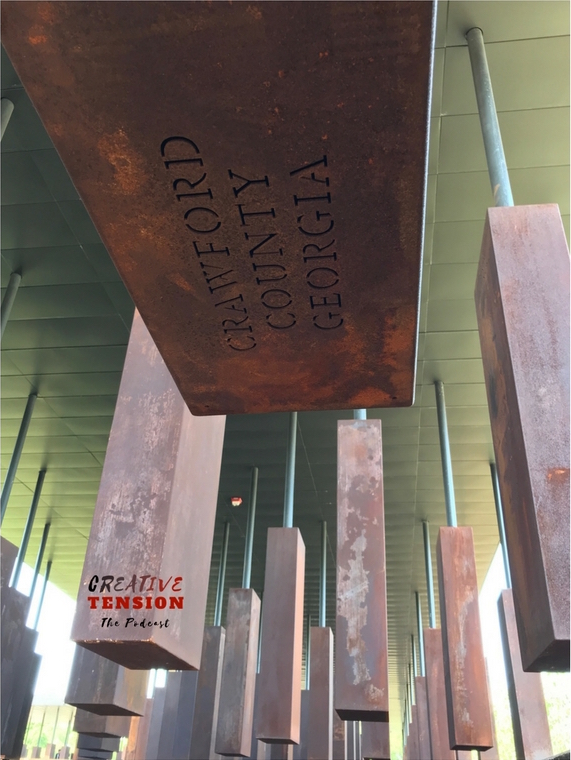

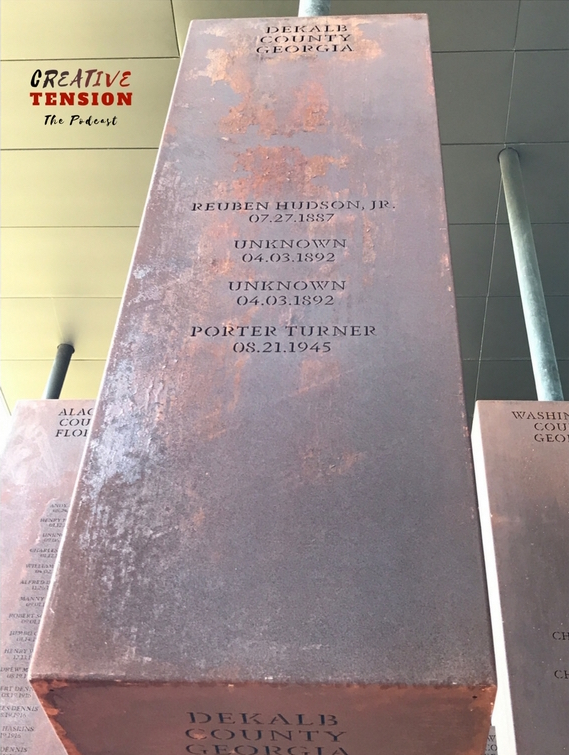

There are 800 steel monuments. There’s one monument for every county in the country where a documented terror lynching took place. Each monument is 6’ high and contains the names and dates of persons lynched in that county. There are over 4,200 victims memorialized at this site.

As I turned the corner and walked upon the first of the monuments, I’m not sure how I felt. I decided I would take my time and weave through the monuments, with the goal of reading the names of all the lynching victims. I wanted to say their names.

The first monument I encountered was for Burke County, GA:

- Edward Welsh - 03.20.1877

- Richmond Roberts 12.17.1882

- Joe Nathan Roberts 06.-.1947

Given the monument’s steel composition, it already carried that weathered and rusted appearance of an object that has been through some things.

Then I see the monuments for Colleton County, SC…Wilcox County, AL…Pike County, GA…Calhoun County, GA…and I begin to wonder, what happened? What happened to Emma and Lillie Mike in Calhoun County on 12.1.1884? What was their story? Why would someone want to take their lives? Are they still remembered by their ancestors? Did the Mike family leave Calhoun after the lynchings? Were they afraid that if they left, more violence would be directed at family and friends who stayed? Each name has its own story that reverberates through the generations.

As I continued, I began to see surnames that were familiar. John Belin 1.27.1898 - Florence County, SC. I snapped a photo of the monument and texted it to my friend Rev. Toni Belin-Ingram. Her dad’s family is from Marion, South Carolina, which is one county over from Florence County.

I walked a little further and came across the memorial for Dorchester County, South Carolina. I’d been keeping a look-out for Dorchester, Berkeley and Sumter counties because that’s where my parents were raised. On the Dorchester monument, I saw the name John Fogle 11.28.1903. My Aunt Anna (my mother’s sister) married into the Fogle family and a large number of Fogles live in neighboring Orangeburg County. I texted my cousin Terrel and sent him a photo of the monument and he intends to do research into his family’s connections to the late John Fogle.

As I was moving through the first wing, I noticed a family being ushered through the courtyard and into the memorial. There were EJI staff members with them, along with a cameraman. Being a journalist and researcher, I decided to double-back and follow them, from a distance. They went to one of the monumnets I had passed at the beginning of the memorial. It was clear they were going to see the name of a loved one on one of the monuments. My initial inclination was to record the moment, but that’s when it hit me. This is truly a sacred space! It should also be a safe space. It was not my place to record them in their personal moment of discovery, grief and connection. As the older woman hugged the monument and wept at seeing the name of her loved one etched into the steel, I said a silent prayer for her and her family and I continued my journey.

As I walked down the first wing and made the right turn onto the second wing, the floor began to slope downward. The monuments were increasingly raised off the floor. They were now hanging. You could still weave through them, but by the end of the second wing, they were full above my head. This was my second moment of revelation. These large monuments were serving as proxy for the strange fruit (hanging bodies) that existed all over this country: Some hanging from gallows or tree branches; others brutalized until death and still other burned alive.

As you enter the 3rd wing, you are greeted with 2 walls of placards (probably more than 50). Each placard providing us with insight into just how perilous it was to be Black in America. The multitude of reasons why women, men and children were killed in the most brutal of ways was jaw dropping.

The Lynching Memorial is certainly a sacred place; however, it’s also a place of discovery and connection. It’s a place where the present can connect with a past that has been hidden, muted and all too often forgotten. It’s also a place of empowerment. An empowerment that can only come from knowing and embracing one’s ancestors and their struggles.

The Lynching Memorial is more than a museum or piece public art,, it is a place to remember. To remember the victims and say their names. To remember their lives and the impact of their deaths on their families and communities. To remember the violence and brutality of this nation’s not so distant past. To remember what human beings can justify doing to other human beings. To remember the reality of American History.

The Lynching Memorial will mean different things to different people, at different times. Yet, each of those things will transform your life forever.